作为旧时云南象征之一的茶叶,是如何发展至今的?How did tea, as one of the symbols of Yunnan in ancient times, develop to this day?

Pu erh Tea Record ", written by Lei Pingyang, Chongqing University Press, July 2022 edition.

Pu'er has 6 "Tea Horse Avenues"

To all parts of Yunnan Province, Xizang and even abroad

In his book "Pu erh Tea Records", the Qing Dynasty scholar Ruan Fu said, "Pu erh belonged to Yinsheng Prefecture in ancient times. The use of Pu erh tea by the Western barbarians dates back to the Tang Dynasty." Mr. Deng Shihai said based on this, "Pu erh tea was already exported to the Western barbarians as early as the Tang Dynasty. At that time, the Southwest Silk Road should actually be called the 'Silk Tea Road' to be correct." In Mr. Deng Shihai's eyes, the Tang Dynasty tea saint Lu Yu introduced famous teas from 13 provinces and 42 states in his "Tea Classic", but missed the Pu erh tea from Yinsheng City in Yunnan. This is truly a regret in the history of tea. Lu Tong, who was also a master of tea tasting in the Tang Dynasty, wrote in his poem "Walking to Thank Meng for Advice and Sending New Tea": "When I opened my mouth, I saw the face of advice, and read three hundred pieces of moon tea." For this famous poem, many tea scholars believe that Lu Tong wrote about Pu erh cake tea like the "moon tea".

Whether Lu Tong wrote about Pu'er tea at that time, from an objective standpoint, perhaps no one dares to draw a conclusion. Yinsheng City is far away in the sky of the barbarian village. As a native of Zhuoxian County, Hebei Province, Lu Tong neither served nor traveled far away. Can Pu erh tea really illuminate his secluded Shaoshi Mountain like a crescent moon in the sky? However, judging from the fact that there were many Tuan Bing teas produced in the Tang and Song dynasties, whether Lu Tong wrote about Pu erh tea or not is not important. What is important is that Pu erh tea may be the only type of tea in the world that inherits the legacy of Tang and Song Tuan tea.

Illustrations on the inner pages of "Pu erh Tea Chronicles".

In the heyday of Pu'er tea in the Ming and Qing dynasties, as a tea distribution center, Pu'er had six "tea horse roads" leading to all parts of Yunnan Province, Xizang and even abroad. These six "tea horse roads" were the main part of Mr. Deng Shihai's "silk tea road". They are in sequence: "Pu'er Kunming Official Horse Avenue", where tea is transported by mules and horses to Kunming, and then transported by merchants in all directions; "Puer Xiaguan Tea Horse Avenue", whereby tea is transported to western Yunnan and Xizang; "Pu'er Laizhou Tea Horse Road", whereby tea leaves pass through Jiangcheng, enter Laizhou, Vietnam, and then transfer to Xizang, Europe and other places; Pu'er Lancang Tea Horse Road "is used to transport tea through Lancang, into Menglian, and ultimately sold to various parts of Myanmar; Pu'er Mengla Tea Horse Road ", tea leaves pass through Mengla and are then exported to various provinces in northern Laos; The last one is the "Menghai Jingdong Tea Horse Road", which is the only "outer line" among the six roads that does not pass through Pu erh distribution. Pu erh tea merchants go directly into Menghai, the main production area of Pu erh tea, purchase tea leaves, and then take the road to Daluo, Myanmar Jingdong, and then transfer them to Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong, China.

Six Tea Horse Avenues, all centered around Pu'er, extend vigorously in four directions: east, west, north, and south. In addition to carrying tea leaves in all directions, the groups of horse gangs and peddlers also overcame various hardships such as crossing rivers, climbing mountains, confronting miasma, and dealing with bandits. They brought the fabrics, salt, iron tools, as well as various life concepts and farming techniques from other places to this remote secret realm.

Yanjin's tea production is evidence of the "Southern Silk Road Tea"

There is no lonely land in the world. The chirping of a bird, the running of an elephant, the howling of a Bengal tiger, every song of a Dai girl under a phoenix tail bamboo, every dusk on Mount Brown... They are all an integral part of Leopold's "land ethics". We can all use telepathy, gaze with our eyes, and listen with our ears from thousands of miles away.

If the 'Southern Silk Road' is really changed to the 'Southern Silk and Tea Road', I would greatly appreciate it. On the conventional map of the "Southern Silk Road", its starting point is Yibin, Sichuan (formerly known as Xufu), passing through the five foot road opened by Li Bing in the Qin Dynasty, passing through Zhaotong and Qujing, reaching Kunming, and then dividing into two routes, either extending all the way to Dali in northwest Yunnan, or heading to Pu'er to Southeast Asia. On the route from Yibin to Kunming, there are few side roads and it is linear, but in Pu'er and northwest Yunnan, it forms a network with scattered connections on all sides. The reason for this phenomenon is not only due to geographical factors, but also because the tea trade played a decisive role in it.

The "1998 Yunnan Province Top 20 Tea Producing Counties (Cities) Ranking List" published in the third issue of the magazine "Yunnan Tea" sponsored by the Yunnan Tea Industry Association can also show us another force in tea trade. The ranking is as follows: Menghai (6909 tons), Jinghong (6708 tons), Fengqing (6508 tons), Changning (3842 tons), Lancang (3540 tons), Simao (2911 tons), Luxi (2880 tons), Yunxian (2873 tons), Yongde (2859 tons), Jiangcheng (2754 tons), Tengchong (2420 tons), Shuangjiang (2259 tons), Lincang (1905 tons), Jingdong (1789 tons), Cangyuan (1763 tons), Gengma (1754 tons), Yanjin (1705 tons), Nanjian (1629 tons), Jinggu (1464 tons) and Mengla (1371 tons).

In this ranking list, it is not surprising that Menghai is the leader, while the old tea areas Jinggu and Mengla rank at the bottom, which can also be understood as the changes of time. Those who have some knowledge of Yunnan's tea industry will find that there is an "alternative" among the 20 counties (cities), which is Yanjin. Other counties (cities) are renowned for their tea production, but only Yanjin produces tea, ranking ahead of Mengla and Jinggu, which is somewhat unbelievable.

Yanjin produces tea, which can be said to be a proof of the "Southern Silk Tea Road". Yanjin is located at the junction of Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, at the throat of the Silk Road entering Yunnan. In the Shimen Pass area of Dousha Township in the county, a well preserved "Five Foot Road" still exists today. The horseshoe marks on the bluestone slab are several inches deep, and when bent down, one can still pull out large piles of rotten leaves and miscellaneous soil, imagining the lively scene of the caravan walking back and forth in the past. According to the "Yanjin County Annals" compiled by Mr. Chen Yide during the Republic of China period and Xiao Ruilin's "Wumeng Chronicle", in the Ming and Qing dynasties, Yanjin only needed to set up checkpoints and collect taxes to maintain county governance. Li Bing opened a five foot road, realizing the dream of "a thousand mile plank road connecting Guanzhong, Sichuan, and Yunnan" in the Qin Dynasty, but also connecting Yunnan with the Central Plains from then on. Yanjin, as a necessary stop on the Southern Silk Road, objectively witnessed the economic exchanges between Yunnan and the mainland. Pu'er tea, as a tribute, must pass through Yanjin before entering the capital. Groups of horse gangs and porters who came from Kunming, Qujing, and Zhaotong must pass through Yanjin before they can go to Sichuan or the Central Plains. In 1940, China Tea Yunnan Company established an office in Yibin, Sichuan to "distribute" Yunnan Tuocha, which is the best evidence.

Yunnan tea and Sichuan salt flow continuously towards both ends here. Why do most counties (cities) in the Zhaotong area not produce tea, so only Yanjin and its surrounding counties produce tea? It is not accurate to infer solely from the perspectives of geography and climate. As is well known, the salt reserves in Yanjin do not have mining value. However, due to the enormous economic benefits demonstrated by the old salt mines, Yanjin has also opened salt wells to extract salt. In the book "Dian Hai Yu Heng Zhi" written by scholar Tan Cui in the Qing Dynasty, tea was once referred to as the "great grain of money"; The Pu erh Prefecture Annals recorded the specific amount of tea donations collected by the Qing government. These historical records accurately reflect the economic value of tea in social life at that time. Yanjin was connected to the bustling tea market in Kunming to the south, and to the tea district in Sichuan to the north. There was also China Tea Yunnan Company providing "support" in Yibin. How could it be unaffected? According to an article in the "Yanjin County Annals", the tea in Yanjin was originally small leaf tea, but later changed to large leaf tea, and as a result of this variety change, the yield increased by 20%.

The hometown of large leaf tea is now Xishuangbanna and Simao, and the introduction of Yanjin tea has a solid foundation for the saying 'the road of southern silk tea'. We can also say that before the Qing Dynasty, perhaps due to the thriving tea trade, the Yunnan Plateau was firmly maintained within the golden economic network of the "Southern Silk Road" and was not completely forgotten by the world.

Tea is a symbol of ancient Yunnan

From an economic perspective, Yunnan, in its old days, largely relied on tea, brass, and cinnabar to demonstrate its existence to the world. The "Continuation of the Long Compilation of Yunnan Gazetteer" once wrote:

This province is a famous tea producing area. Pu'er tribute tea is famous throughout the world. In the heyday of the past, even the six major tea mountains produced tens of thousands of dan annually. Rich in flavor and quality, with excellent variety. Kuangdian is a mountainous country with poor agricultural production, and the climate, soil, and terrain of the whole province are hardly suitable for tea. Therefore, in terms of the environment and quality of Yunnan tea, it has the potential to seize the international market and compete with tea producing countries such as India, Ceylon, Japan, and Java in the world market. Due to its remote location, traffic congestion, and farmers' adherence to traditional methods, the cultivation, manufacturing, and packaging of Yunnan tea are all crude and rudimentary... The main production areas of Yunnan tea are mostly located in the southwest corner. Originating from the six major tea mountains, it extends to the highlands of Ailao, Mengle, and Nushan on both sides of the Lancang River. In other words, its development trend is generally moving from Jiangcheng, Zhenyue, Cheli, Fohai, Wufu, Liushun and other counties in the south of Simao to Lancang, Jingdong, Shuangjiang, Mianning, Yunxian in the northwest, and finally to Shunning... The six major tea mountains are also known as Youle, Gedeng, Yibang, Mangzhi, Manzha, and Mansha; Or it is called Yibang, Jiabu, Yaogu, Manzhuan, Gedeng, Yiwu; Or it can be called Yibang, Yiwu, Barbarian Brick, Mangzhi, Gedeng, or Jiabu, but it is unknown which one it is. These six tea mountains were once under the jurisdiction of Simao Hall, which also belonged to Pu'er Prefecture, so people from other provinces generally named Dian tea as' Pu'er tea '. In fact, Pu'er does not produce tea. The tea produced in the twelve Banna areas along Simao's border was named after the name of the administrative region... (Dian tea) is sold in the following ways: Tuo tea in Sichuan, brick tea and tight tea in Xizang (heart shaped), round tea in Siam, Nanyang and Hong Kong (round cake shaped, seven cakes in a barrel, seven cakes in a barrel, also called seven son round tea), and ancient tea Manzhuang tea in Xizang is sold as free tea in the province

In the book, it is also known that Pu'er not only does not produce tea, but is not a distribution center for tea. The real tea distribution was completed in Kunming and Xiaguan. Because at that time, Yunnan tea was mainly sold in Sichuan, Kang, and Tibet, with sales to Annam, Siam, Myanmar, Southeast Asia, and other coastal provinces along the Yangtze River. Kunming and Xiaguan were the two major markets for Yunnan tea, with the former entering Sichuan through the Zhaotong Yanjin line and the latter entering Sichuan through Tibet and Lijiang. Little known is that Menghai (formerly known as Fohai) was once a distribution center for southern Yunnan tea. According to the Annals of Twelve Banna written by Mr. Li Fuyi, the commodities in Twelve Banna, taking tea as the main commodity, are sold to India, Bhutan, Nepal, Myanmar, Xizang, China, Hong Kong and other places by the Buddha Sea for 36000 packs a year, while only about 1000 packs flow to Simao. If this data does not hide human imagination, it would be very cruel for Pu'er because people have become accustomed to the saying that Pu'er is a tea distribution center. But the problem is that when Li Fu used data, what he said in the "Continuation of Yunnan Tongzhi Changbian" was the official "convincing words".

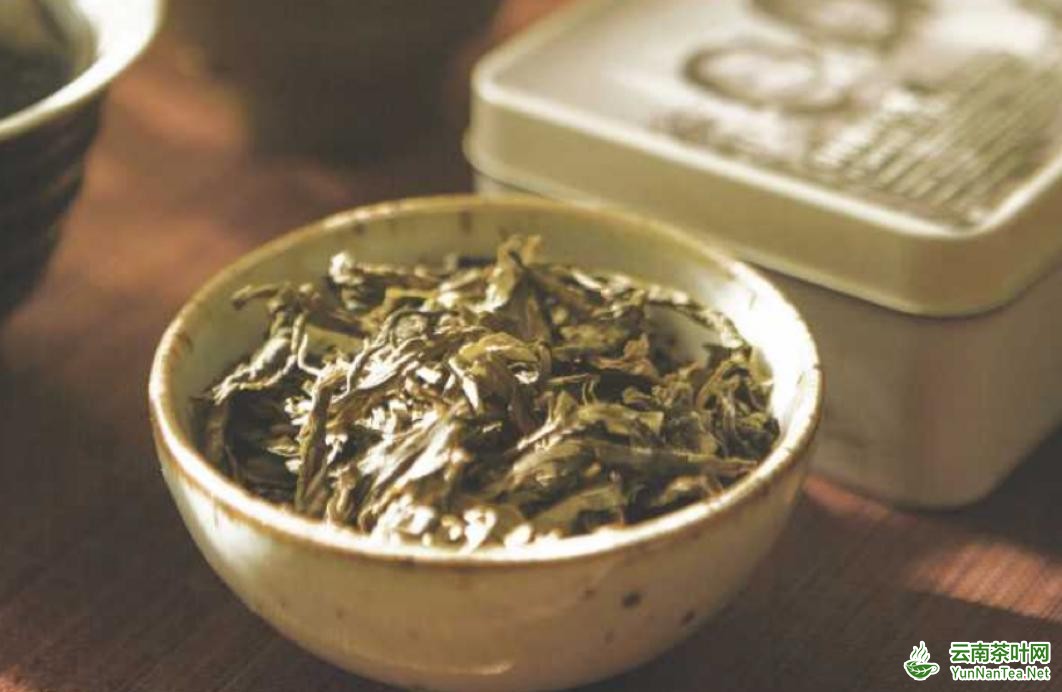

Illustrations on the inner pages of "Pu erh Tea Chronicles".

Anyway, whether it's the Kunming, Xiaguan, Menghai distribution or the Pu'er distribution, regardless of the passage of time and the ups and downs of the world, tea, as a symbol of Yunnan in the past, has become increasingly clear. It is not only active in tea producing areas such as Xishuangbanna, Simao, Lincang, and Baoshan, but also serves as a rapidly running elf on the "Southern Silk Road" network, fully intervening in every corner of Yunnan. Especially when it moved north to Sichuan, it quickly activated the entire mountainous region of northeastern Yunnan.

The spiritual dimension born from tea,

Still carries the meaning of 'strict hierarchy'

During the Tang Dynasty, the master of tea tasting, Lu Tong, wrote a poem about seven bowls of tea, conveying seven different levels of tea drinking:

One bowl moistens the throat, two bowls break the loneliness.

Three bowls searching for dried intestines, only five thousand volumes of text.

Four bowls are sweating lightly, and all the troubles in life are dissipating into the pores.

Five bowls have clear muscles and bones, and six bowls are full of immortal spirits.

I couldn't eat seven bowls, but I felt the clear breeze blowing in my armpits.

Where is Penglai Mountain located? Yukawa Zi, riding on this gentle breeze, I want to go back.

The seven realms are sublimated one by one, and it is difficult to comprehend them unless one is a literati or a person with a calm and charming heart. A history of Chinese tea is a spiritual history that will never have an end, and the practice of tea is guided by principles such as setting the environment, selecting tea sets, using water, choosing tea, brewing tea, and even achieving the same goal of tea meditation - every step and procedure is a result of vulgarity, elegance, and mystery. Tea immortal Lu Yu said about tea: "There are nine difficulties in making tea. One is to make it, the other is to say goodbye, the third is to use utensils, the fourth is to use fire, the fifth is to use water, the sixth is to roast it, the seventh is to finish it, the eighth is to boil it, and the ninth is to drink it." The perfection of the process from making to drinking is definitely not comparable to the extravagant drinking of peddlers. The Ming Dynasty was a hedonistic era in Chinese history. Zhang Yuan said in his book "Tea Records": "Drinking tea is precious when there are few guests, but when there are many guests, it is noisy and lacks elegance. Drinking alone is called 'God', two guests are called 'Victory', and three or four are called 'Fun'. How many tea people can reach the three words' God ',' Victory ', and' Fun '?

Writer Lin Yutang also had a tea theory and summarized ten key points from a technical perspective:

Firstly, tea leaves are delicate and prone to decay, so when dealing with them, they must be very clean and kept away from alcoholic beverages, aromatic substances, and people who carry such odors. Secondly, tea leaves should be stored in a cold and dry place. During the humid season, spare tea leaves should be stored in tin cans, while the rest should be stored in large cans, sealed and stored well. When not in use, they cannot be opened. If they become moldy, they must be lightly dried on a low flame, and a fan should be gently used to avoid yellowing and discoloration of the tea leaves. Thirdly, the art of brewing tea lies in selecting water, with mountain springs being the top, river water being the second, and well water being the second. The water in the sink comes from the embankment because it belongs to the mountain. Springs are very useful, so they are very useful. Fourthly, there should not be too many guests, and only elegant people can appreciate the beauty of cups and pots; Fifth, the main color of tea is clear with a slight yellow tint. For overly strong black tea, it is necessary to add milk, lemon, mint, or other ingredients to balance its bitterness; Sixth, good tea must have a lingering aftertaste, which can be felt about half a minute after drinking tea when its chemical components interact with the body fluids; Seventh, tea should be brewed and consumed immediately. If left in the pot for a while, it will lose its flavor; Eighth, tea must be brewed with freshly boiled water; Ninth, all spices that can mix with the true flavor must be eliminated, at most only slightly adding cinnamon or substitute flowers to suit the taste of some enthusiasts; Tenth, the tea with the highest flavor should have a milky fragrance like a baby's. ”

Compared with the opinions of Lu Tong, Lu Yu, Zhang Yuan and others, Mr. Lin Yutang's discourse, although more lively and imbued with the scent of ordinary people, is not something that everyone can do. The spiritual dimension born from tea still carries the meaning of "strict hierarchy".

Tea has no grade,

There is no way to drink tea

I started with Pu erh tea when it comes to tea. My hometown is in northeastern Yunnan. The village where I was born is located at the border of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan provinces. It has always been a good place for material distribution, and there have been countless horse gangs since ancient times. My father's memories are vivid: in the depths of those black and white times, on the official road behind the house, those horses carrying heavy loads, one after another, walked from dawn to dusk, from dusk to dawn again. Sometimes, I always see drunk horsemen pulling the horse's tail and stumbling past. Occasionally stopping, those blood red eyes always stare at the little daughter-in-law in the village, so the series of romantic affairs are like wild grass, cut and cut, and no one can clean them up. As a result, there have been repeated battles with each other, and many horsemen have not died on the most dangerous road, but have died in a sudden desire.

Illustrations on the inner pages of "Pu erh Tea Chronicles".

However, regarding these matters, the father is just an observer and does not have much say. As a witness, my grandfather is better able to explain the origin and destination of those horse gangs. Most of the people who can buy horses to join the gang and travel between Dianchuan are wealthy. My grandfather is a porter. He belongs to the group of people on the Yunnan Plateau who lack the money to buy horses and have to get involved in business to support their families. In the years when I was just beginning to understand, he had grown old and had a strange temper due to the hardships of life. If only time is used as evidence, his age is not enough to deform his body, like an old machine, with every component malfunctioning and covered in rust. In my impression, he always shuddered from the cold, never buttoning up his long shirt in any season, always wearing it to reveal his wrinkled chest, and sitting by the fire pit all the time, making the flames burn brightly and shining directly on his chest. Grandpa looks like a big bird flying through the rainy season, baking his wet wings.

Occasionally, my grandfather would take out a round tea called "Seven Child Pancake Tea" from the pillow. It was only later that I learned about it. With a trembling hand, he would pull open the cotton paper, break off a small lump, and enjoy the roasted tea.

At that time, tea was a luxury item. Our mother taught us that drinking tea was a bad habit and would make our stomachs black. Therefore, we all thought that our grandfather was not a good person. The tea jars used by my grandfather for roasting tea are from Weining, Guizhou. It is said that only the tea jars produced in Weining have the most fragrant and mellow tea taste when roasted. Grandpa first preheated the tea can in the fire, then held the tea leaves in his left hand and held the tea can in his right hand, shaking it back and forth on the fire. His eyes were fixed on the mouth of the can until a faint mist or fragrance floated out of the jar covered in tea stains, and a faint red color appeared at the bottom. He then put the tea leaves in. Then, the right hand holding the can shook violently, occasionally stopping abruptly, shaking again, stopping abruptly, entangling endlessly. He sniffed and watched with his eyes, and only injected boiling water when he thought it was just the right time. With a "plop" sound, he lifted the tea can and poured out the tea, often only taking a dark, creamy sip or so. The creamy droplets in my grandfather's mouth, I couldn't imagine the taste, but his constantly smacking lips showed me happiness.

Illustrations on the inner pages of "Pu erh Tea Chronicles".

In addition to eating roasted tea, Grandpa also developed the habit of eating dry tea during his career as a porter. Go out to bask in the sun, bring a small lump with you, and when you get addicted to tea, put it in your mouth and chew it carefully. The appearance of chewing tea leaves is equally obsessed.

In Grandpa's account, due to fear of robbers along the way, he followed the caravan of wealthy families on every "up Yunnan, down Sichuan" journey as a porter. Leaving the house, he picked out chives from Qujing and sauce from Zhaotong, and walked all the way down the plateau, selling them among the towns in the Sichuan Basin. When the burden was empty, we bought salt from Zigong, Sichuan, and then walked all the way to the plateau. We rested briefly in Zhaotong and spent 13 days walking to Kunming, followed by Yuxi, Mojiang, Pu'er, as well as Jiangcheng, Menghai... until all the goods in the burden were sold out. Sometimes, when Grandpa picks up goods, there are no restrictions on the variety. For example, when he reaches Kunming and sells out of salt, he will also exchange some other goods and then head south.

Before his grandfather passed away, he still called Jinghong Cheli and Menghai Fohai, intermittently mentioning Jiangcheng. He could also recite this rhyme: "There is a county in Jiangcheng, Yunnan, where the yamen is like a pig stable, the lobby is covered with boards, and the four gates are audible." In his impression, Jiangcheng County was too small. When we arrive at the tea area, Grandpa naturally won't return empty handed. He often has to pick a load of tea leaves and go back to Sichuan. Pu erh tea in Sichuan has the largest sales volume, and the "Song Round Tea" produced by Song Yunhao Tea House, which was established in the early years of the Guangxu reign. However, my grandfather found its quality to be poor and insisted on choosing "Can Xing Brick Tea" first, and gradually switched to "Red Seal Round Tea" produced by Fohai Tea Factory

My grandfather is a porter who specializes in tea and belongs to the category of drinking by the sea. However, due to several rounds of tea sales around the Dai calendar year, he has formed an inseparable bond with tea produced by Kexing Tea House and Fohai Tea Factory. Now thinking about it, it makes me feel that there is a kind of bloodline inheritance in the underworld. Before his death, he was still obsessed with the "Seven Son Cake", although it was no longer the "red seal" and "green seal" of the past, but this kind of heart that only a child could have made me feel helpless. This also reveals the truth that tea has no hierarchy, and there is no way to drink tea, only the spirit is eternal. The tea of Lu Yu, the tea of Lu Tong, and the elegance of Zhang Yuan and Lin Yutang can all be regarded as private matters, arising from one's heart and being held by oneself. But the Pu erh tea from Menghai is highly praised by many tea masters, but it does not hinder my grandfather, who is a porter, from enjoying it. There must be a reason for this, and it has become the source of my writing.

This article is selected from "Pu erh Tea Chronicles" and has been edited and edited compared to the original text. The subheading was added by the editor and is not owned by the original text. The illustrations used in the article are all from the book. Authorized by the publishing house for publication.

Original author/Lei Pingyang

Excerpt/An Ye

Editor/Li Yongbo

Proofreading/Lucy